How does the ‘Science of Reading’ help with literacy?

How does the ‘Science of Reading’ help with literacy?

In a classroom of learners, you might wonder why it is that some children seem to easily pick up reading, while others struggle.

The reality is that children are individuals, with unique abilities, and different ways of processing and learning information. The reason that some children pick up reading more easily, is that the way we have been teaching literacy (reading and writing) in class has suited their particular learning style.

In New Zealand, this is showing up as a serious concern in the classroom. A March 2023 article in the New Zealand Herald about issues in our school system, reported on Unicef’s findings that over a third of our 15-year-olds do not have basic proficiency in literacy. Serious issues have also been found in younger pupils, with 37 per cent of Year 4s found to be behind curriculum expectations in both reading and writing and in Year 8, 44% were behind in reading and 65% were behind in writing. More information can be found here.

Dr. Ralph Wesseling, Director and Development Manager of NumberWorks’nWords, says that for many children, mainstream teaching methods have missed the mark.

“Over time the way we teach reading has evolved. For the past 10 to 15 years, most approaches to teaching have been focused on a ‘Balanced Literacy’ approach, which draws on a combination of elements from ‘Phonics’, ‘Whole Word’ and ‘Whole Language’. When it was introduced, Balanced Literacy was a big improvement from teaching methods that only focused on one or another of these methods. However, while it worked well for most of the children, the remainder still struggled.

“To help us to better understand how we learn to read, scientists, from a number of disciplines, have developed a method to teach reading called the “Science of Reading”. Reading as a complex skill involves multiple brain areas and cognitive processes, including visual perception, attention, memory, language processing, and executive functions. The Science of Reading was developed based on many years of converging evidence from thousands of studies.

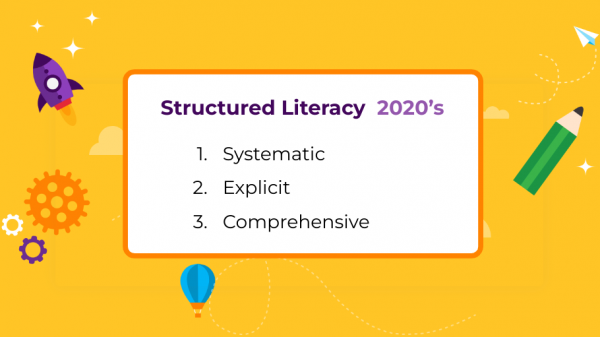

“The evidence from the Science of Reading supports a move to a new 'Structured Literacy' approach which is systematic, explicit and comprehensive, to ensure no component of learning to read is overlooked when teaching,” says Dr. Wesseling.

So what does a systematic, explicit and comprehensive Structured Literacy approach look like? And what are the components of learning to read? To understand this better, let’s first look at some history of how learning to read has evolved and the different methods of teaching.

A history of reading

The early days of literacy began with teaching the alphabet and reading the bible. Around 1570, English educator John Hart, reformed the teaching of literacy by developing a Phonics approach. Phonics refers to the way letters sound individually or when combined, and this new approach focused on the relationship between letters and sounds.

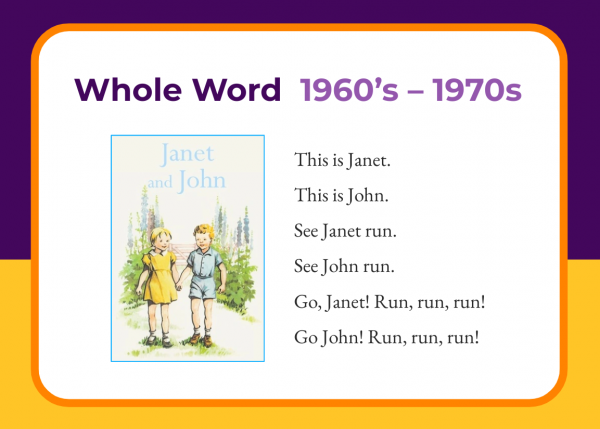

In the 1900s, a more balanced approach began to be argued for, and in the 60s and 70s a ‘Whole Word’ approach became popular, which involved learning whole words rather than the sounds in them.

Flash cards were introduced to help students memorise high-frequency words, then practise reading those words in context with LOTS of repetition in readers (for example the Janet and John series), where pictures helped children guess the context of the words.

In the 1980s the ‘Whole Language’ approach gained popularity, as educators decided that students would be more motivated by reading authentic and interesting texts. The proponents of the Whole Language approach also believed that phonics instruction was not critical, because students would discover letter/sound relationships naturally through lots of reading.

In this approach, Phonics was taught more in the context of writing and spelling, rather than reading. It wasn’t a systematic approach, the idea was that children would ‘discover’ the necessary letter/sound relationships. There was a focus on reading to children, and they were also encouraged to write about their experiences using invented spelling.

So how effective are these teaching methods?

Unfortunately, with any of these methods individual; Phonics, Whole Word, or Whole Language, there are some pitfalls our young readers can fall for.

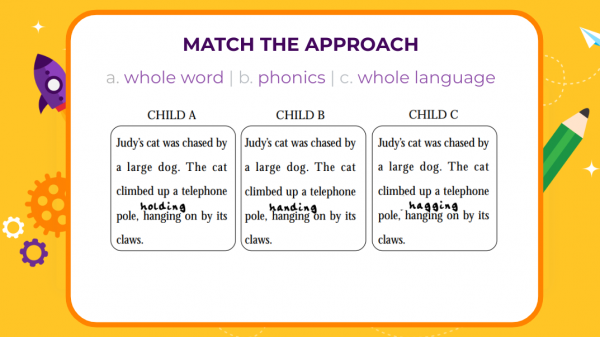

Here we have examples of reading errors from three different children. In each example, the handwritten text represents the word that the child read aloud when asked to read the text.

Take a look and see if you can guess which teaching approach, a) Whole Word, b) Phonics, or c) Whole Language, was used for each child.

Child A - has been taught to read with c) Whole Language - here the child has guessed a known word that makes sense given the context, but isn’t the correct word.

Child B - has been taught to read using a) Whole Word - they can remember ‘hand’ as one of their high-frequency words, but don’t yet recognise ‘hang’.

Child C - has been taught to read with b) Phonics - they have sounded out the letters, and are familiar with a hard ‘G’ sound, but don’t yet know the ‘ang’ sound.

A ‘Balanced Literacy’ approach - 1990s to 2000s

The Balanced Literacy approach combines the best elements of Phonics, Whole Word and Whole Language into teaching. It encourages students to use all of these strategies; memorisation, context, and sounding out the word, to work out unfamiliar words during reading.

Children would use an ‘MSV’ approach for guessing unfamiliar words when reading:

Does it make sense? (Meaning)

Does it sound right? (Structure)

Does it look right? (Visual)

But is Balanced Literacy the best way to teach children to read?

Dr. Wesseling says the research findings that have emerged from the Science of Reading, show that the Balanced Literacy method is not systematic, explicit or comprehensive enough for some struggling young readers.

Many children still struggle to learn to read with a Balanced Literacy approach. Those with reading disorders like dyslexia have REALLY struggled with Balanced Literacy and a significant 10% of the population is dyslexic.

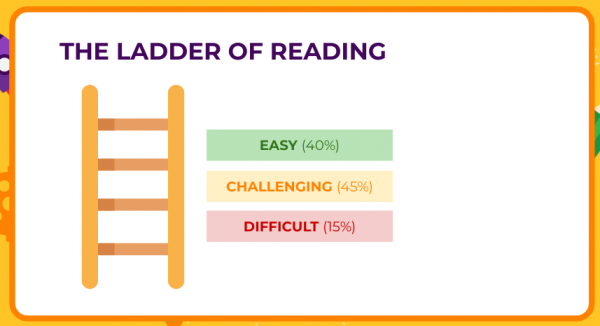

The Ladder of Reading shows the statistical distribution of how easy or hard children find it to learn to read. This shows that 60% of our children really struggle!

For children who fall into the ‘challenging’ orange category on this ladder, a Balanced Literacy approach will still eventually work, however, it will take much longer. Whereas they will make much more rapid progress with more explicit, systematic instruction.

The emergence of the Science of Reading

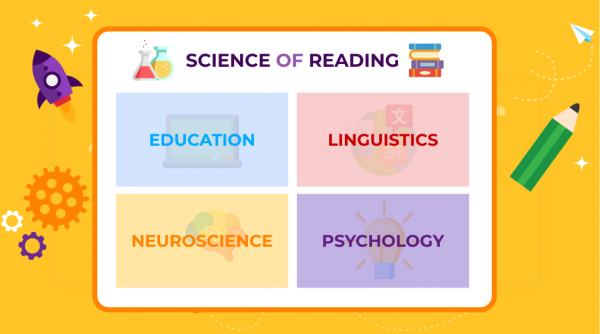

The Science of Reading research draws from 4 fields of study:

- Linguistics - Study of the structure of human language

- Psychology - Doing experiments to understand how people think and learn best

- Neuroscience - Structure and function of the human brain in learners of all abilities

- Education - Applying the research from these 3 areas, to develop effective teaching methods and instructional materials to maximise student outcomes.

The Science of Reading research has proven that the best approach for teaching children with dyslexia is actually the best approach for teaching ALL children to read. This approach is known as ‘Structured Literacy’.

So what is Structured Literacy?

Structured Literacy is a teaching approach derived from the Science of Reading research, that ensures the components of reading are taught in a way, that:

Is systematic - it teaches skills in a carefully organised sequence,

Is explicit - we don’t assume children will pick up things naturally

And is comprehensive - covers all the important components of literacy.

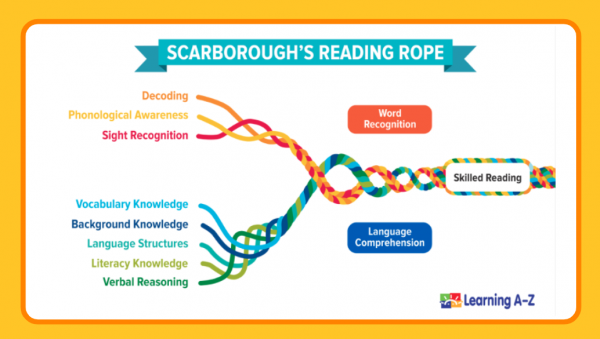

So what are the components of reading? A simple view of reading is that the skill of reading comes from two strands, ‘word recognition’ and ‘ language comprehension’.

- Word recognition is made up of three components: Decoding, Phonological Awareness, and Sight Recognition.

- Language comprehension is made up of five components: Vocabulary Knowledge, Background Knowledge, Language Structures, Literacy Knowledge, and Verbal Reasoning.

Scarborough’s Reading Rope illustrates the components that makeup word recognition and language comprehension, which become more integrated as skilled reading develops.

So what’s an example of a Structured Literacy approach to teaching?

An example is teaching the alphabet. Dr. Wesseling says that one approach is to do it in alphabetic order, but that is not the most effective method.

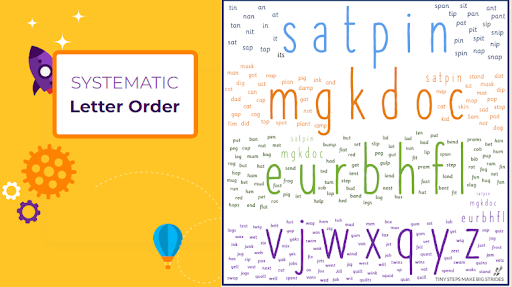

“A better approach is to use SATPIN. With SATPIN letters are learnt in groups with the high-frequency letters first. This means that students can start learning to read and spell words as soon as possible."

“Letters that can be easily mixed up with other letters are not taught in the same group."

“Another method is the Carnine approach. This is a systematic method that builds grapheme-phoneme knowledge (in other words the sounds that letters make) from simple to complex.

“The Carnine list of letters separates visually and auditorily similar letters so students aren’t learning b and d close together, or having to discern the difference between /i/ and /e/ at the same time. It also first teaches the sounds of letters that can be used to build the most real words e.g. m, s, a, t,’ explains Dr. Wesseling. (For more information, follow the link.)

These examples are just a small sample of how a Structured Literacy approach can be applied to teaching literacy.

Our journey toward Structured Literacy

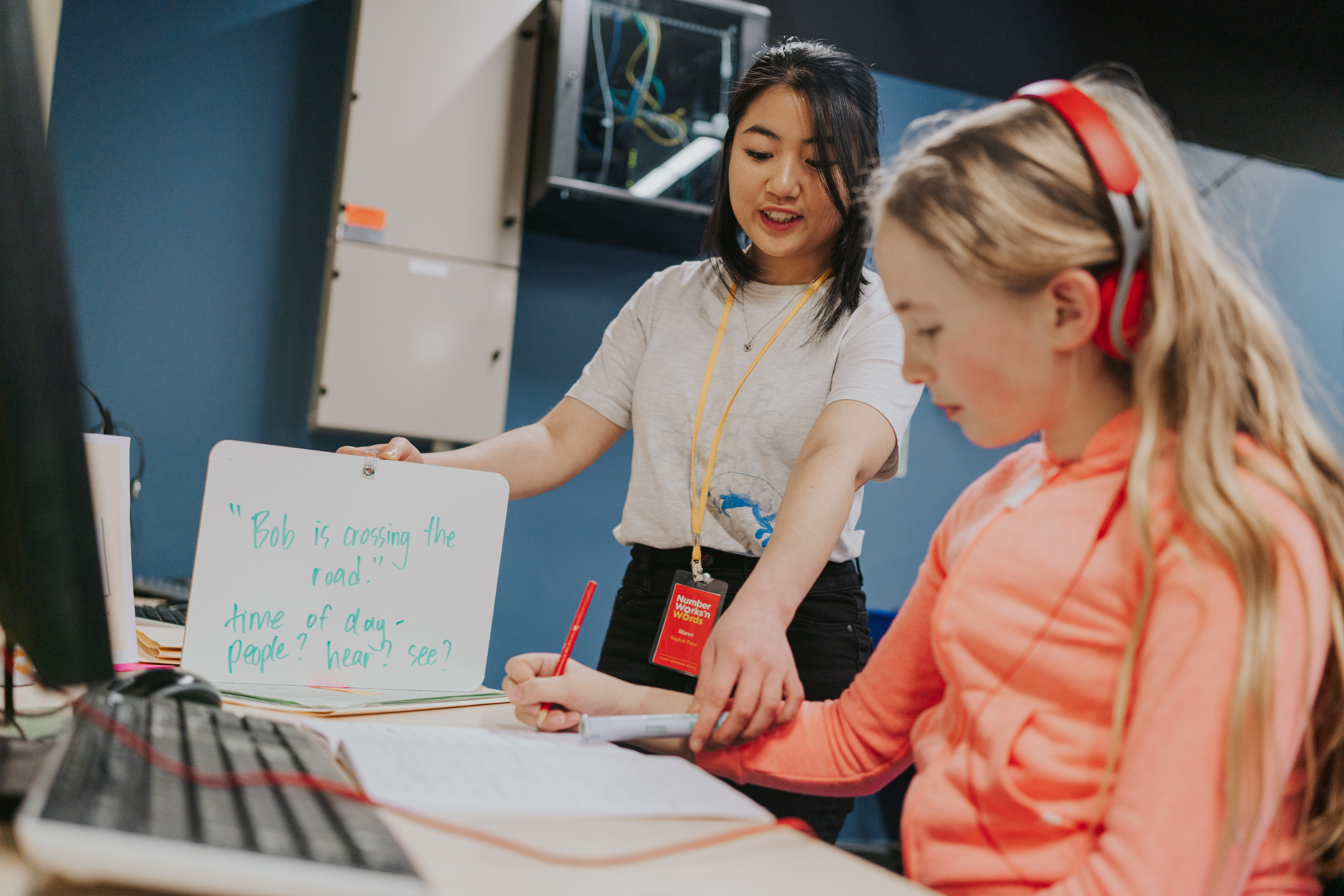

“At NumberWorks’nWords, we are currently on a journey towards a comprehensive Structured Literacy programme for our English tuition. This process is about adapting and refining our current content to ensure we align with the latest research.

“When we first implemented our English tuition programme Balanced Literacy was the current best practice. However, our tuition programmes have always had advantages over standard Balanced Literacy curriculums. Our programmes are explicit; we don’t assume that children have the knowledge they don’t. Our programmes are systematic; we have data about individual learners that allows us to tailor their learning programmes to their individual needs. In addition, our tuition is comprehensive; we have comprehensive knowledge and expertise in the components of reading, as identified in Scarborough’s Rope and we cover all these aspects.

“The improvements we are currently making are based on research that has emerged from the Science of Reading, to ensure that we better align with a Structured Literacy approach. We’re excited to be working on this new content to deliver more effective results for our learners,” says Dr. Wesseling.

If your child is struggling with literacy we can help. Our English tuition supports students ages 5 - 16 with their education. English tutoring with NumberWorks’nWords improves school results and boosts confidence, through a personalised approach to tuition which caters to students of all abilities. To learn more about English tutoring at NumberWorks’nWords, book a free assessment today.